Hydration! More important than you realize.

When you start a wildlife rehabilitation course, you spend a LOT of time on hydration and fluids therapy. Calculations. More calculations. ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, when do we get to the hard and interesting stuff?’, thinks the novice.

But during my rehabilitation training as in my first year, I can’t tell you how important this lesson proved true. It cannot be stressed enough: HYDRATION is VITAL. Stop and read that 10 times. Let it soak in 😉.

Seriously, without proper hydration:

To make matters worse, most animals arrive at rehabilitation dehydrated. Their dehydration can worsen due to diarrhea from a number of causes: an intestinal parasite, well-meaning but uninformed rescuers providing improper formula, or the formula not being slowly increased in concentration. Stress can also contribute to dehydration. Sadly, dehydration can be deadly.

But what is HYDRATION?

Isn’t it just water? No. While animals (including humans, as mammals) are mostly water, the water in our bodies has the same salinity as the ocean and is loaded with minerals (evolutionary legacy from the primordial sea).

Hydration refers to providing the body with adequate fluids to maintain physiological functions, which occur at the cellular level. Every cell depends on water solutions of specific dissolved salts at particular concentrations, within a narrow pH range. These salts are electrolytes. Electrolytes are present in fluids both inside and outside your cells. Throughout the body, there’s a constant and dynamic flow and exchange of water and electrolytes.

Electrolytes are charged minerals that are essential to life. Their positive and negative charges help conduct electricity between cells and balance fluids (more technical version). If this cellular balance and electrical signals are disrupted by abnormal water/electrolyte balance, the consequences can include shortness of breath, muscle contractions or twitching, cardiac arrhythmia, fatigue, mental changes, organ malfunction or failure, and/or death.

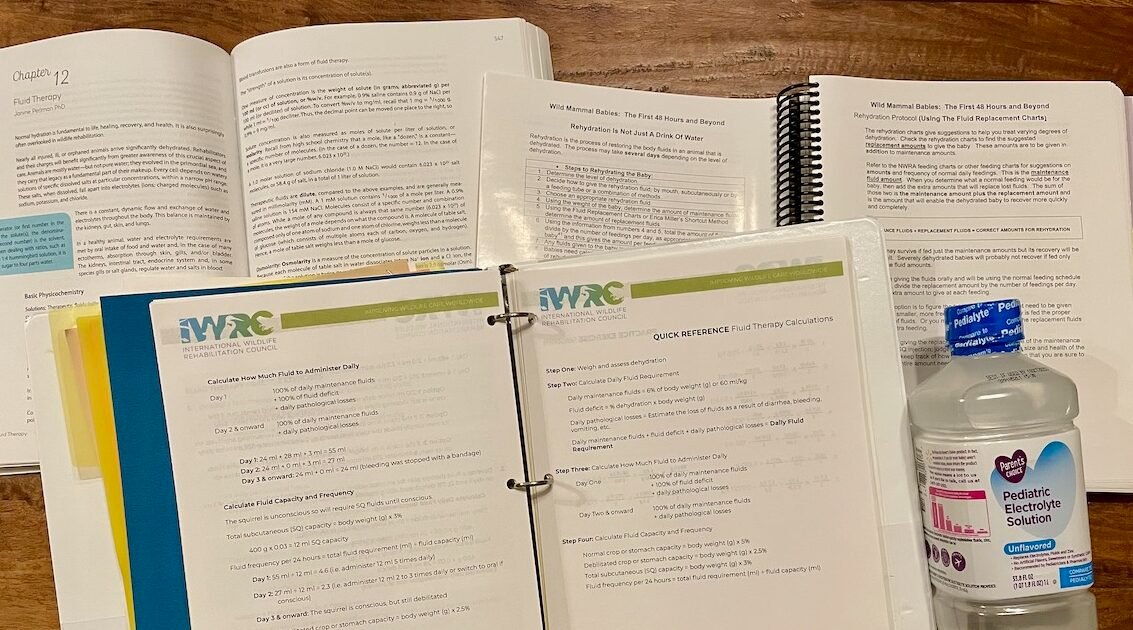

Fluid Therapy: The Basics

Fluid therapy is rehydration, restoring water and electrolyte balance. It involves providing appropriate solutions with careful measurements of fluid intake and frequent assessments of body weight, hydration status, and overall condition. Rehydration may take several days, depending on the level of dehydration.

In addition to the minimum daily fluid requirement, rehydration involves correcting deficits (level of dehydration) as well as addressing abnormal losses (e.g. from injury or illness). Neonates and newborns are especially vulnerable to dehydration, and this is worsened if they’re housed in an incubator without added high humidity, or if they’re naked (not yet furred), leading to fluid losses through their thin skin.

“The life-saving results of rehydration include increased circulation of all fluids, normalization of body temperature, increased physical strength, mobility and alertness, prevention of permanent kidney damage, normalization of gastrointestinal function, improved wound healing and immune function, detoxification and elimination of metabolic waste by increased liver and kidney perfusion.”1

I cannot stress enough the criticality of proper rehydration for the survival (and thriving) of rescued wildlife. Speaking from experience, if there’s one mistake you are likely to make as an inexperienced rehabilitator, this is it. There’s a reason why we spent so much time on this exact topic in training. If you’re new to rehabbing animals, please seek education on this.

What if you need help NOW?

This blog post is not intended to give you a comprehensive education on fluid therapy — details like how much to give, how often, how to determine levels of dehydration, what fluids are optimal under specific circumstances, when to give oral vs. subcutaneous injections, etc. Rather, I aim to stress the importance of this topic and help you appreciate its urgency and gravity. As mentioned, wildlife training classes, go-to books, and online documentation from wildlife organizations (often found in Facebook support groups) cover this extensively.

That said, I do want to help those just getting started who have found themselves with rescued animals and need guidance on where to begin NOW. Here’s a starting point:

Mix the following:

Bring this mixture to a warm (not hot) temperature, ~90-95F (recall that human body temperature is ~98F).

Offer fluids every 2 hours, or as often as every hour if the animal seems thirsty or dehydrated. See Step 2, under START HERE, to determine stage of development.

- If the eyes are open but not wide: Offer fluids with a feeding syringe (no needle). TSC sells 1mL syringes, which are inexpensive. Offer drop by drop, ensuring no fluid enters their noses. Do not offer liquid in a lid at this stage of development. There are also numerous youtube videos if you search for syringe feeding baby opossum (or possum).

- If the eyes are wide and they have white in their fur (thicker fur): You can offer fluids in a shallow lid.

- If the eyes/slits are not opened: Contact a rehabilitator or an admin in the Facebook groups listed here for immediate assistance. You can try the 1mL feeding syringe mentioned above, but these animals are often too small and may require tube-feeding.

Please, NO Food until properly hydrated.

Lastly, a common mistake made before we even receive animals is kind hearted people wanting to FEED them. It’s understandable, humans empathize. If we hadn’t eaten in a while, we’d want tasty treats too. But recall that organs, including the gastrointestinal system, don’t function properly (or at all) when dehydrated. Hydration must come first (along with warmth and stress reduction) BEFORE food (which includes formula).

If a wildlife baby arrives at a wildlife rehabilitator after being fed ANY food or formula, we must first flush their system with fluids BEFORE slowly starting them on formula (at low concentrations). This means that feeding them actually delays proper nutrition.

So if you’ve rescued an animal, please coordinate with a rehabber before feeding it, and absolutely HYDRATE FIRST.

Basics are best.

Whether you’re considering volunteering and training in wildlife rehabilitation or have just rescued wildlife and are figuring out what to do, it’s the basics that matter most and form the foundation. Heat/Warmth. Hydration. Low Stress. These factors are CRITICAL to saving a life and should not be underestimated.

Now, everyone, get up and go drink some water (with some electrolytes mixed in). Your cells, organs, muscles, skin, and brain will thank you.

Footnotes:

- Quote from IWRC, “Wildlife Rehabilitation: A Comprehensive Approach” ↩︎